Panta Rhei

performance & "strategy" update (free to read)

Happy New Year, everyone.

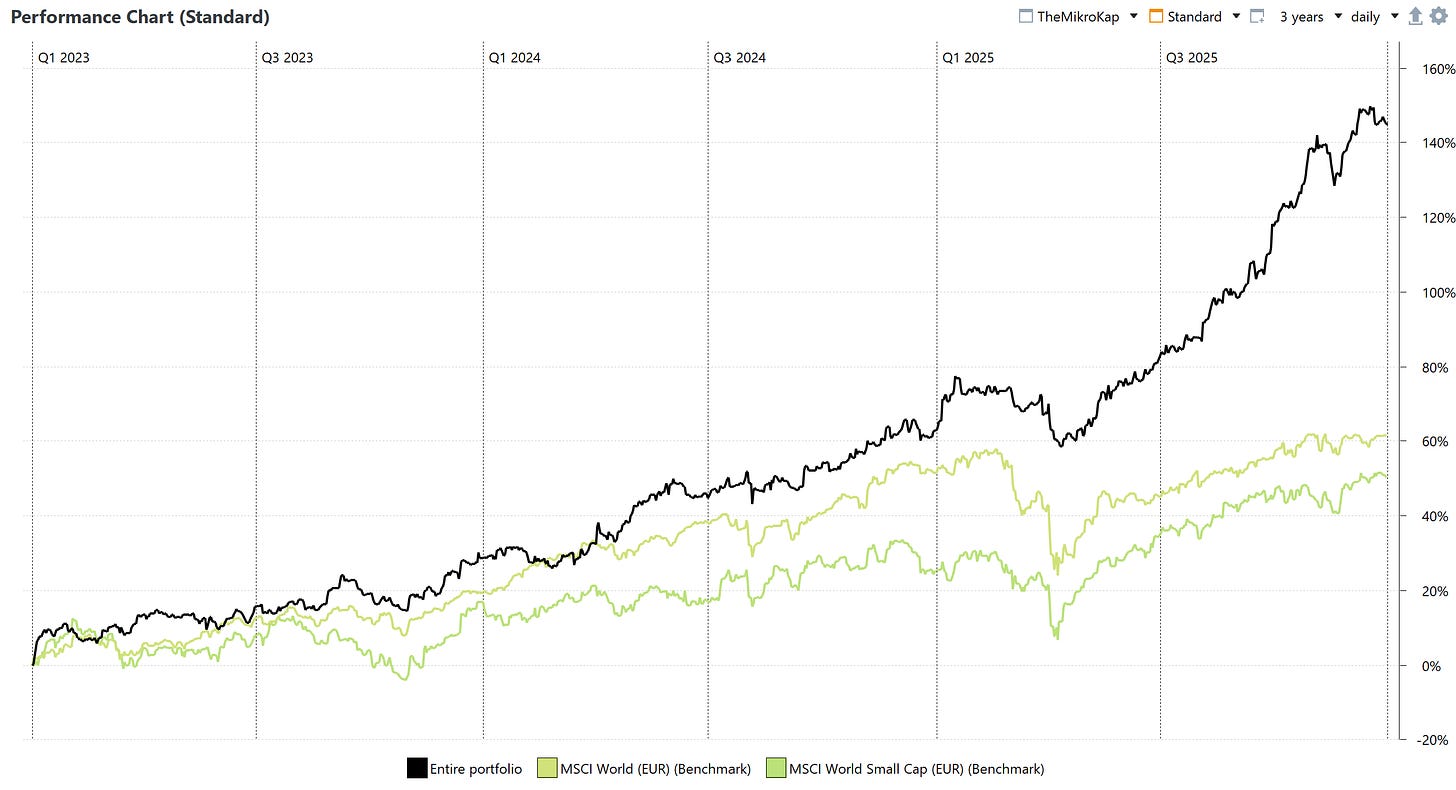

With 2025 behind us, I’ve now wrapped up my third full year of sharing stock analyses and every buy/sell decision on Substack. Performance over that period:

2023: +29%

2024: +26%

2025: +51%

These are pre-tax returns in EUR (my base currency). And the actual tax bill in 2023 and 2024 was—and should remain for 2025—small, thanks to Croatia’s favorable capital gains rules (12% on capital gains and dividends, 0% after holding a stock for over two years, and no wash-sale rules).

With 2026 ahead of me, I wanted to reflect on my investing strategy—if you can even call it that. A quick caveat first: while a 37% CAGR over three years is something I’m happy with, three years of public performance obviously doesn’t qualify me to give advice, so please don’t treat this as such. This is simply one guy writing things down, to look back in ten years and see how much he’s changed and, hopefully, improved.

More importantly, there are many roads to Rome. The strategy and style that work for me won’t necessarily work for you, and vice versa. If you handed me $1B to run with a focus on options flow, or swing trading, I’d almost certainly underperform. At the same time, I know there are plenty of investors who absolutely crush it using exactly those approaches.

Although the more I invest, the more I believe there are exceptions to almost every rule in investing, the four main pillars of my approach haven’t really changed. I wrote about them in more detail roughly 2.5 years ago in My Life in Value article for anyone interested.

In short, I still prefer:

Illiquidity. I like under-followed companies and obscure setups where I’m not trying to outsmart or compete with “professional investors,” but instead be early to something they’re not yet paying attention to.

Downside protection. I strongly believe that buying things well matters more than buying good things.

A clear path to value realization—accelerating growth, improving capital allocation (used to be my main focus), or material corporate actions that eventually force the market to agree with my valuation work.

Doing deep enough work to be confident in points 1–3, and to know that a lot has to go wrong for the investment not to work out.

But for this article, I want to switch the focus to a few “frameworks” that have become more and more important to my investing style since I wrote that article. And to things I didn’t expect to matter as much when I first started investing, or even when I first started writing this blog.

Let’s start. I realized…

It’s often much easier to make a good add decision than a good initial buy decision.

This is for a few reasons. First, at least for me, true comfort—or discomfort—with an investment only comes once you’ve actually put money behind it and started to hold the stock. You see how the business performs, whether management executes on what they said, and you start noticing things you didn’t previously know existed or thought didn’t matter much. With the release of each new filing, you can then check whether what you believed needed to happen for the investment to work is, in fact, happening.

I think this is especially true in micro-caps, where things change far more often than in large-cap land—and when they do, the impact on risk-reward is much larger than it would be for a $20B-revenue company with three product categories and eight product lines. To give an example from just the past year or so (which I think many of you are already familiar with):

December 2024

$LDB.MI exiting its risky France business to fully focus on an underpenetrated HVAC market, using a sensible strategy of acquiring stable local businesses from retiring owners at attractive prices.

January 2025

$ALCO shifting strategy away from unrewarding citrus farming toward rezoning and selling its land—valuable assets that had effectively been “locked” on the balance sheet. Under a management team with a good track record of returning sale proceeds to shareholders.

November 2025

$EVC’s AdTech segment accelerating for a fifth consecutive quarter since the split into Media and AdTech, reaching 104% revenue growth last quarter and accounting for 63% of total revenue.

Or even just last month

$ICCC abandoning a 25-year pursuit of FDA approval to refocus on its high-quality core business.

In all four cases, something material changed that either took the downside off the table, improved the upside ahead, or both. And what’s attractive about underfollowed setups like these: you don’t have to worry that (a) good news gets priced in immediately, or (b) most investors even recognize that the news is good in the first place.

This is exactly why I like doing deep work before initiating a position—because without it, I wouldn’t recognize the change as an opportunity or be able to separate signal from noise. And it’s also why I’m so annoying about mentioning the Substack chat: I genuinely think some of the earnings / news coverage there can end up carrying more alpha than the initial research report.

So, in short, I like adding when the odds improve and a future that was once uncertain now has fewer negative scenarios. Or more likely and more material positive ones. Even if the price has already moved a bit.

Which brings me to another point.

2) No investor ever steps in the same micro-cap twice, for it’s not the same micro-cap and he’s not the same investor.

Sorry for the twist on Heraclitus’ quote, but I think this is also why doing A-Zs, getting familiar with as many companies as possible, and then staying on top of them matters so much. Even if it means you’re mostly reading useless 8-Ks.

Just as an initial small buy might turn into your largest position or something that needs to be cut entirely. In the same way a watchlist name that has been sitting in your “investing universe” for five years can, with one change, suddenly deserve your attention or your capital.

This is why many of my current ideas come on the back of historical due diligence, and why I try to adapt as results come in and theses evolve. In fact, usually some of the best opportunities end up being the ones that weren’t your cup of tea when you first found them, but over time—through strategic pivots, management changes, better capital allocation etc.—the setup improves while the share price goes nowhere. At that point, the risk-reward often looks far better than when you first came across the idea.

Okay, another related point.

Long consolidation

While I’m not a chartist (and don’t think I ever will be) reading Ted Warren in 2024 made me start paying attention to stocks consolidating near 52-week highs or 52-week lows. By consolidating, I mean a period of more than a year (the longer, the better) where a stock is range bound, usually accompanied by low volume.

I never invest solely based on a chart or trust it blindly, but I’ve noticed a pattern: in setups like these, the risk-reward at the beginning of the stock range is often very different from the risk-reward at the end of it, when I’m actually looking at the setup. And despite real fundamental progress and business changes happening beneath the surface, investors tend to ignore them. Either because they’re too impatient adding to what feels like “dead money,” or because they sell out in frustration for the same reason. This is especially true in bull markets, when everyone around seems to be making money left and right.

There were two good examples of this in Italy this year.

$COM.MI (the stock) had been consolidating for about four years until this spring. Over that period, management successfully integrated the huge WPG acquisition, lifted the (normalized) margin profile of the business, and paid down the “unwanted” long-term debt that came with the deal. One quarter later, the Q2 2025 results showed that the deterioration in the agriculture and industrial end markets had finally stopped and the cycle was close to a bottom. And, with a cleaner balance sheet, management then moved to acquire Nabtesco, further consolidating the industry. As a result, the stock was up more than 50% within six months.

$LDB.MI’s chart was also consolidating around a 52-week high and went nowhere for more than a year, even as the thesis was de-risked by exiting France and the upside improved materially through HVAC acquisitions completed in H2 2024. Only once that showed up in the H1 2025 results (something the market is now clearly excited about) did the stock reprice, rising roughly 130% since spring. Even though the impact these acquisitions would have on the financials was already apparent by the winter of 2024.

Again, this is just a bias around game selection, similar to a rule I outlined in my My Life in Value article about using low beta for illiquid, non-cyclical businesses as a north star when looking for underfollowed companies. I’ll still invest in businesses with charts that look nothing like this, and I’ll still buy stocks that aren’t low beta. In fact, I may even look back a few years from now and realize I simply had a good outcome that had nothing to do with a long, consolidating chart. We’ll see.

There’s a difference between thinking long term and holding long term.

While I approach investing with a longer-term view and a thesis (whether around business prospects, a special situation, or something else) that’s often a few years out, I’ve come to realize that holding something long term rarely ends up making sense for me. At least for my style and the returns I’m trying to achieve, while avoiding taking on excessive risk.

I like flipping a lot of rocks, which naturally brings new and interesting ideas onto my radar. And when those ideas offer a risk-reward that looks meaningfully better or more asymmetric than what I currently hold, it feels foolish not to reshuffle with the aim of maximizing IRR.

That said, I still think buy and hold can work if (a) you don’t have the time or desire to do a lot of rock-flipping and ongoing maintenance due diligence, and (b) your initial thesis on a business and the management’s ability to execute was SPOT ON.

Personally, I think combining a long-term view with a willingness to cut when the IRR math worsens and replace a position with a better idea is superior. The catch is that this approach really only works if you’re constantly turning rocks—finding new ideas and judging their risk-reward against a growing set of opportunity costs from both portfolio holdings and watchlist names. Over time, that process naturally makes you pickier and leaves you with only what you believe is truly “best” in the portfolio.

Also, given everything I’ve written above about how changes disproportionately impact micro-cap businesses, I think it would be silly for me to buy something and then not look at it for some arbitrary amount of time—just to feel like Buffett buying American Express, or to say I have a three-bagger over five years instead of a one-bagger over two. The first sounds more impressive, even though the math clearly favors the second—41% CAGR versus 25% CAGR.

Of course, this is the ideal case—moving away from something that’s worked but where the upside is now smaller or more uncertain. In practice, turnover is often also the result of mistakes I’ve made in assessing the risk-reward, or of being confident about the wrong assumptions in my valuation work. When I realize that’s the case, I get out quickly.

I don’t mind looking stupid on the internet, or exiting a stock I once thought was far more attractive than the facts that followed suggested. And if I catch myself rationalizing too much or getting emotional about someone pointing out flaws in my work, that’s usually a signal. It’s usually my body telling me there’s disconfirming evidence I hadn’t seen before, and that I should reassess immediately—or get out.

Unrelated, but this is exactly why the third pillar of the investing strategy I outlined in My Life in Value matters so much, and why “buying things well” beats most other approaches. When you end up wrong on a thesis—and you inevitably will—it’s far better to be wrong in an obscure value trap that no one ever believed had a bright future than to be wrong in a beloved GARP stock where everyone shared the same growth story. When that consensus breaks, there’s usually no downside protection left to shield you from the mistake.

Additionally, I think this approach fits my concentrated style of investing because I can’t afford to sit through multiple contraction in a large position and come out unscathed—or rather, I don’t want to if I don’t have to. I don’t mind selling winners, and I don’t mind selling losers. And I tend to prefer ideas that I’d consider one-foot hurdles—things that make sense to hold when they’re dirt cheap or cheap, but not when they’re fairly valued. Those are much easier to sell than wonderful businesses bought at fair prices, where returns depend on long-term compounding and where exit timing is inherently harder. And, of course, I’m lucky enough not to face overly punitive short-term capital gains rules in Croatia.

For example, I now hold zero positions that I held in H1 2023, even though keeping them would have resulted in a decent enough IRR.

Curiosity + attention span = “huh” moments

Although I’ve outlined some things here that have worked for me and that I think should continue to work, this was still an unpleasant thing to write. Because…when it comes to investing, I don’t think anything is set in stone, and I stopped believing in “investing strategies” some time ago.

Rather, what I truly believe is an evergreen truth for anyone fishing in the micro-cap seas is that your “edge” comes down to two things. The first is curiosity—something Greenblatt describes particularly well in his special situations classes, on page 245:

“Oh, really? Let me take a look.”

The second is attention span—the ability to research diligently.

So if I had to describe my investing process in a single sentence, it would be this: read, read, read, pass quickly on most ideas, and keep going until something good, cheap, or unusual makes me say “huh?” out loud, at which point I dig deeper to figure out what the “anomaly” is really about.

Opening my eyes to what might be an opportunity on my desk, then doing the detective work needed to figure out what actually matters and how that shapes the risk-reward of a given investment. Ultimately building enough conviction to decide whether to pass, follow along, or make the bet at the appropriate size.

Since I’ve already mentioned Greenblatt, it would be a pity not to mention Buffett as well. And Brett Gardner’s book on Buffett's Early Investments probably captures this best:

“His fluid analytical process allowed him to jump from investment to investment, always focused on finding value. From figuring out whether American Express’s competitive position was impaired due to the Salad Oil scandal to handicapping the odds of the British Columbia Power deal closing, he focused on solving the right problem. The prevailing thinking on Buffett far too often tries to box him in by repeating cliches about finding great businesses and great management teams. But it ignores how flexible he was in the variety of opportunities he scooped up, as well as the different types of research he performed to uncover information.”

And that’s it for the current Mikro Kap style—if you can even call this stream of thoughts that. It helped me reflect on a few things, but it’s probably not the best use of my time to do often, which is why I won’t be repeating this regularly.

Still, many of you have asked whether my investing style has changed over the years, so I hope this was a helpful and interesting enough answer for those who did.

If you’re still reading, happy New Year again. And thanks for sticking around!

I’m back to looking for those “huh” moments.

David

The Mikro Kap uses information sources believed to be reliable, but their accuracy cannot be guaranteed. The information contained in this publication is not intended to constitute individual investment advice and is not designed to meet your personal financial situation. The opinions expressed in such publications are those of the publisher and are subject to change without notice. Consult your financial adviser to understand whether any investment is suitable for your specific needs.

I may, from time to time, have positions in the securities covered in the articles on this website and reserve the right to buy or sell any securities mentioned in this article at any time, without prior notice.

This is not a recommendation to buy or sell stocks. Do your own due diligence.

Great performance David, some great points made too.

Happy New Year David! I really liked reading this. Charts are the last thing I personally look at before investing. If there isn’t a clear breakout yet, I will set an alert on the volume and the Moving Averages crossings. This helps increased my IRRs in 2025 as limited money went to stocks that didn’t move. Definitely worth as part of portfolio management of existing positions in my view as well.