Four Horsemen of Japanese SaaS

research report

So…

Why am I writing about B2B SaaS companies? What makes that model attractive?

(in no order)

they sell software that companies and their employees rely on every day—and can’t really do their jobs without. Once it’s embedded in an organization’s workflow, switching becomes extremely difficult. In Wall Street terms, it’s “mission-critical.”

as the last “S” in SaaS implies, the “service” model means subscriptions—and subscriptions mean recurring revenue. That recurring nature makes the business far more predictable and its unit economics clearer, both for managers allocating “excess” capital and for investors trying to assess normalized profitability through the cycle. It also makes the business easier to run and more resilient to industry or economic downturns (unless your customers go bust, of course).

another related point is that customers typically pay upfront—either annually or in monthly installments—which creates float and makes cash flow run ahead of net income, especially during the growth phase.. That allows the business to expand more easily than it otherwise could, without needing to tap debt or equity markets.

a sticky customer base, a low subscription cost relative to customers’ overall expenses, and a lack of alternatives compelling enough to justify the hassle of switching often translate into strong pricing power and gross margins of 60–70% or higher—plus excellent net margins once the business scales. As the customer base grows, each additional customer typically brings in far more revenue than the fixed costs (IT, admin, etc.) or OpEx associated with serving them (assuming the company isn’t running a dumb sales-and-marketing strategy). This creates significant operating leverage. And combine that with low churn and you get a highly-profitable, durable business. A 10% annual churn rate (about 0.83% monthly) implies an average customer lifespan of roughly 10 years.

VMS (vertical market software), built to serve industry-specific needs, stands out because it typically faces more limited competition than horizontal SaaS—at least for the new clients. These niche verticals tend to end up with oligopolistic software offerings, and bigger non-VMS players don’t bother entering since the TAM is too small to move the needle for them.

on the other hand, horizontal SaaS stands out for its resiliency in downturns and its ability to further monetize the existing customer base through upsells and cross-sells—without needing heavy ad spend to acquire new customers.

most of the required growth and maintenance CapEx is limited to hardware/IT equipment and office build-outs, which means net income can be returned to shareholders without hindering the company’s ability to grow.

everything is delivered through the cloud, so you can scale the business from a single office. There’s no need for teams traveling around to install software on-site like in the old on-premise days.

most companies I’ve looked at have no meaningful customer or supplier concentration, so no single party has the leverage to squeeze pricing. And as a SaaS company grows its customer base, the value proposition often strengthens. Because, if you listen, those customers will give you the feedback you need to continuously improve the product.

But why am I writing about Japanese SaaS specifically? What makes it interesting?

(in no order)

the opportunity set among listed SaaS companies in Japan is wider than in any other country. Using the (vague) screening criteria I applied, I came up with 40 companies in Japan, compared to only 19 in the U.S. and Canada combined—and coincidentally, also 40 for all of Europe.

one of the main reasons so many of these companies ended up listed is that Japan’s local VC industry was (and still largely is) small and reluctant to fund SaaS. That pushed companies wanting to scale to go public earlier than usual—and it also kept competition for first-movers lower than you’d typically expect.

related, many of these companies took advantage of the COVID-era frenzy, going public at absurd valuations while posting inflated ARR growth. Now the sentiment has swung almost to the opposite extreme. Despite finally putting up a solid year, most Japanese SaaS stocks have been hammered once again over the past 2–3 months.

Japanese people aren’t exactly your San-Francisco-style early adopters. Digitization in Japan still lags much of the developed world. Many companies literally keep files on paper or run their operations in Excel. Culturally, the country leans toward manufacturing and hardware, not software.

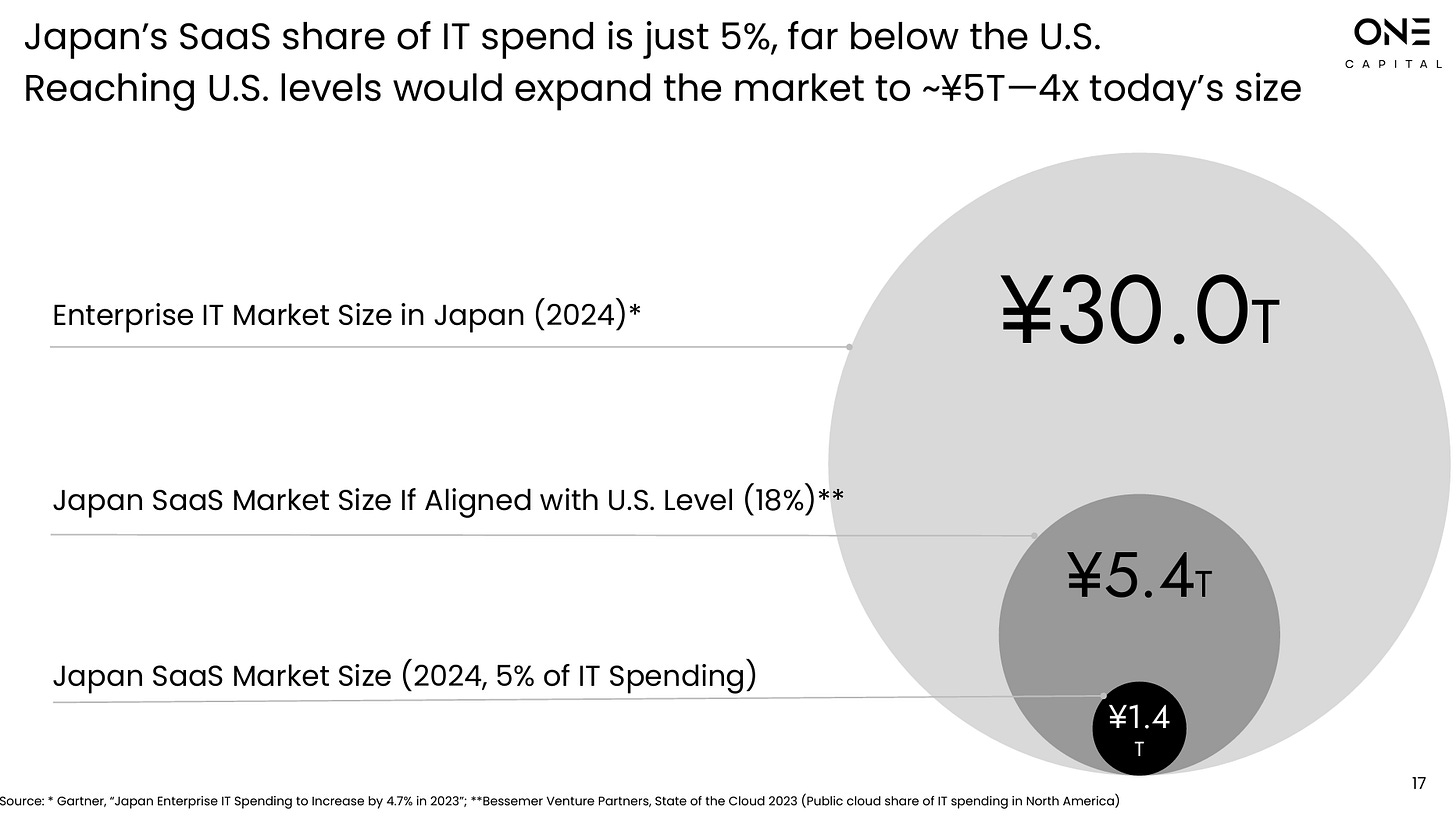

Japan was slow to digitalize internal processes, and the firms that did modernize often did so through customized on-premise software installed by large system integrators, which was an industry standard for decades. Only recently have companies begun shifting to cloud-based SaaS, with SMEs leading the way. Even today, Japan remains far more under-digitalized—or under-clouded, if that’s a word—than other developed markets.

there are studies floating around suggesting that by the end of this year, more than 60% of mission-critical corporate IT systems in use will be over 20 years old. Replacing these outdated systems and going through a proper “digital transformation” should drive significant demand (especially for the two horizontal SaaS providers covered in this report). Enterprises know this, and the government has been pushing in the same direction for quite some time.

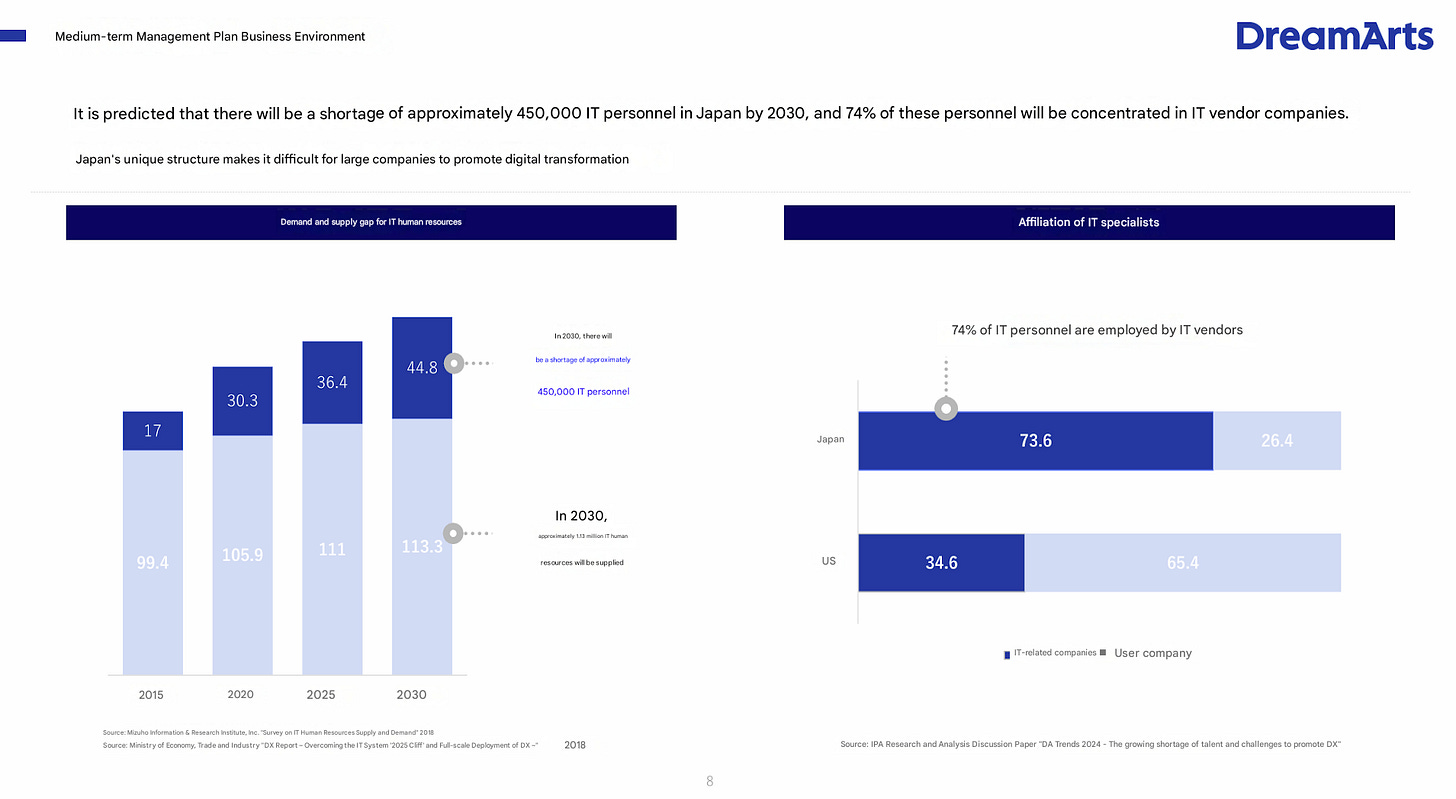

related to the point above, an aging population and a severe shortage of skilled IT workers have made it necessary to automate redundant processes and boost the productivity of existing labor through software.

a unique culture creates unique needs, and those local nuances make it difficult for global software companies to enter and compete effectively. This is especially true for VMS players, which usually operate in markets too small to attract serious competition. They’re not going up against the Microsofts or Oracles of the world.

a lack of quality entrepreneurs and a weak risk-taking culture means the few who can scale and execute stand out even more. Again, this isn’t San Francisco—leaving a stable job at a system integrator to start a SaaS company is frowned upon in most Japanese families.

I also think it’s part of Japanese culture not to switch solutions once they find something that “works.” The average monthly churn among the Japanese SaaS companies I’ve looked at is noticeably lower than that of their U.S. counterparts. For reference, two companies on this list that actually disclose churn come in at just 0.6% and 0.34% per month.

Japanese investors aren’t used to understanding software stocks—they prefer net-nets, dividend names, and manufacturing companies. Meanwhile, low liquidity and the lack of English filings make these stocks unappealing to most foreign investors managing large pools of capital, even though they might view the underlying businesses as high-quality and cheap. These ignored pockets of the market are exactly where I like to look.

lastly, based on the SaaS micro-caps I’ve looked at outside Japan in the past, Japanese names tend to be more profitable, grow faster, and trade cheaper on average. I didn’t bother to “backtest” this, but I’m pretty sure you could verify it with a screen.

As with any broad framework, there are plenty of exceptions to what I’ve outlined above. Probably none of these points apply universally, and each company still requires individual work to confirm whether the ideas actually fit.

Also, not everything is rosy—there are, of course, real risks. For example, for VMS businesses, even though you might enjoy 75%+ gross margins compared to ~60% for horizontal SaaS, you also run a higher risk of saturating your TAM much faster. Horizontal SaaS doesn’t face that same ceiling, but it does need far more scale to reach VMS-like net margins, and it has to deal with heavier competition in its sales channels—everyone trying to pitch a “better” solution to get a foot in the door of a large Japanese enterprise.

And since Japan isn’t San Francisco, founders don’t have access to anywhere near the same depth of technical talent you’d find in the Bay Area. That’s why you need to be super careful when a Japanese SaaS company talks about expanding overseas and competing with American peers—or avoid those stories altogether.

The last major risk, of course, is technological change, including everyone’s favorite buzzword: AI. Some will adapt, but many will be disrupted.

Still, I hope this 1,000-word bullet-point “brainstorm” helps explain why I’ve spent the past month digging through the roughly 40 small Japanese SaaS names that initially came up in my screen. I narrowed that list quickly, added a few I’d already researched, and ended up with 32 companies worth keeping on a watchlist. After spending 2–3 hours on each, I trimmed that group to 13 that merited deeper work. From there, I went through those carefully and ultimately came away with 4 I like most.

Two are VMS names, two are horizontal, and all four are micro-caps. Together they make up the Four Horsemen of Japanese SaaS—or at least that’s what my not-so-creative title calls them.

Let’s dig in.